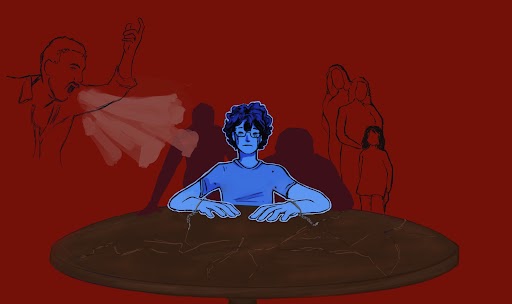

Machismo seen in Hispanic youth isn’t something that is just left behind when immigrating.

The effects of machismo and, by extension, sexism, can be seen in families as well as schools and extracurriculars.

With Ritenour’s Hispanic population steadily growing, questions on how exactly machismo can affect the students are rising as well. With machismo creating a culture of enforcing an exaggerated valuation of masculinity and denigration of femininity, the dynamic of how Ritenour looks at and understands gender roles is being put in the spotlight.

The Hispanic youth have noticed the effects of macho culture on themselves and others as well.

“The effect of machismo can vary from person to person,” junior Johcer Godinez said. “I’ve seen people let it get to their heads and make them treat others as below-average people.”

How machismo defines gender roles

According to the National Library of Medicine, in a study with 390 adolescents, masculinity has a poor/negative association with emotional regulation and a strong/positive association with reactive and proactive aggressive behaviors.

This can be due to the fact that when masculinity is encouraged in boys, it includes encouraging fighting as a display of strength and power. Many boys are taught that aggression is the best way to preserve someone’s ego in the machismo culture.

“Putting up with any form of emasculation, like even something as small as getting beat in a game of football, can be a basis for fighting,” Ritenour alumnus Michael Madrid said. “I’m personally not a fighter, but when (boys) are younger we’re taught if anyone messes with us, the consequences are not important, what’s important is to show others that we won’t put up with anything.”

The effects of aggression aren’t just left on the swings though.

“It gets worse as you age,” Madrid said. “In high school, when you’re with other guys it’s very easy to want validation from them. Since they’re also taught it’s good to be aggressive you all start sort of enabling that kind of behavior together. Then, when you get to college, you meet guys who are cemented in their aggressive way and they have the physical capability to really do some damage.”

This sentiment is typically only encouraged in men, senior Alejandra Arango notes.

“Fighting was something seen as ‘distasteful’ and ‘unclassy’ for the girls, so we’d get put in a box but we did learn how to deal with our anger differently,” Arango said.

This encouragement for not fighting in girls leads to femininity being more associated with emotional regulation. However, this doesn’t mean that women don’t also experience the aggressive end of machismo.

“Growing up I experienced my father exhibit controlling aggressive behavior towards my mom, and when she left, I was the main target of this,” Arango said. “He would always place himself as someone me and my mom would have to serve and we were never allowed to go against him because he was who was providing for us. He always asserted that we had to do everything for him, make his food, clean for him, but luckily I was able to leave that when I moved out.”

Machismo and abuse

This aggression fueled by machismo is seen not only in controlling behavior, it’s also in physically and sexually aggressive behavior that often goes unreported or underreported and is treated as taboo.

According to Connections for Abused Women and Their Children, nearly half (44%) of domestic violence cases go unreported, and Hispanic women are especially less likely to report abuse for fear of being deported or having no family to go to.

Statistics for sexual violence are unfortunately similar. According to the National Crime Victimization Survey from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, one in six females ages 13 and older are victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault, and according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 77 percent of Latinas said sexual harassment was a major problem in the workplace.

The shame and guilt associated with speaking up about abuse is something that is also a motif of machismo. When a woman has to speak up about abuse happening to her, she is often met with the sentiment that she got abused because she didn’t accurately fit into her role of being a female in the confines of machismo.

“It’s like it’s viewed as our fault,” Arango said.

Senior Gezel Urbina Torres agrees with Arango, that often the women in Latino culture are cast as the villains due to machismo.

“We’re taught to just listen and follow orders, and if we don’t blindly comply we’re made out to be the crazy ones,” Urbina Torres said.

The effects of machismo on the youth don’t stop there, one of the biggest places machismo impacts is in school.

“Not only are girls expected to prioritize their home life and future family over their career, they’re encouraged to do so too,” Urbina Torres said. “This expectation from a young age can set girls up to have fewer opportunities presented to them and demoralize them from pursuing a career in spaces dominated by men.”

Hispanic women in the workplace

When women do break through in spaces dominated by men, they’re still greatly discouraged from continuing due to gender pay gaps. According to the U.S Government Accountability Office, compared to white male managers, the pay gap for Latina managers was on average 44 cents on the dollar.

Maria Weber, the Program Director of the Master of Cybersecurity and Information Systems in the School for Professional Studies at Saint Louis University also has similar experiences with being a Hispanic woman in a male-dominated STEM space.

“As a young woman, pursuing a major such as computer science and engineering in Venezuela was something not very common. Then later getting my masters in applied analytics in the United States was still quite uncommon. I often found myself being one of the only women in the room and would always feel the need to be ‘on-point’ 100% of the time to be able to seem serious and professional amidst my male colleagues,” Weber said.

Weber also found that while there has been some push in promoting women to follow STEM careers, it’s still not enough.

“The push for education is something that starts when someone is very young, so promoting STEM-related jobs to girls needs to start in childhood. Every child should feel like they have the equal ability to pursue any type of career and parents, along with teachers, should not assume that just because a child is a certain gender they’d thrive in only one type of job,” Weber said.

Weber also mentions how family works with her career.

“Many people believe that an individual has to only choose career or family, however, even though it is very hard work, I’m able to have a fulfilling career and take care of my family, with a bit of help of course. Machismo hasn’t stopped me from pushing for what I want and it shouldn’t scare others who want both as well,” Weber said

Machismo’s effect on men and jobs

Machismo’s effect on what men are pushed to follow in school is something important to discuss as well. Many men are discouraged from going into careers that are female-dominated and are taught to view these jobs as having less value. This negatively impacts those males who want to pursue a career in those female-dominated areas by causing them to also be looked down upon and negatively impacts women who are in those female-dominated spaces by those jobs typically receiving less pay and less respect even with similar workloads seen in male-dominated careers.

“I’ve met lots of other guys who are completely uninterested in their future college major and would probably benefit from changing it, however, these guys usually do what they think is expected of them and would feel shame if they didn’t.” senior Manuel Garcia Medina said.

Even though the effects of machismo are not unfamiliar to adolescents, there is a clear decline in sentiments supporting the alienation of individuals who do not fit traditional macho roles.

“I think we’re free to believe in what we want to believe in and decide how we want to live our lives,” Godinez said, when discussing the topic of individuals who don’t fit the standard roles machismo fits people in.

This idea of individuals accepting lifestyles different from the ones that machismo outlines gets more and more popular each generation, as according to the Pew Research Center, each generation after the silent generation gets about 5% more accepting of boys doing activities associated with girls and vice versa than the last.

The Hispanic youth can also note that traditional masculinity is not an inherently bad concept.

“If the intentions are good, then it isn’t such a bad thing,” Godinez said. “I know I like the idea of me one day doing hard work and bringing money to the family, but I’m not against the idea if my wife wants to work. I’d just prefer if the responsibility only burdened me.”

While machismo still plays a role in today’s Hispanic youth, there’s slowly more self-awareness of the issues that machismo can bring and a change in what is socially acceptable.

“If a woman and man decide to be a homemaker and a breadwinner in a relationship respectively then there’s nothing wrong with that,” Urbina Torres said. “Some people want to live in these roles and that’s totally okay, there just needs to be that respect and understanding that one person isn’t more important than the other.”